Here’s what that deadrise number really says about your boat and its performance potential.

By Eric Sorensen | SOUNDINGS Magazine

We’ve all heard it: the typical conversation between a customer and a salesperson at a boat show that invariably turns to deadrise.

“How much deadrise does she have?” the buyer asks, innocently enough.

“Twenty degrees,” the salesperson answers reflexively, referring to the deadrise at the transom.

Having exhausted his knowledge of the subject, the seller quickly moves along with the buyer to something they’re both more comfortable with: “How about those cupholders?”

It’s a shame because deadrise is important to understand how a boat will perform at sea. The right amount of deadrise, which generally varies from bow to stern, matters. Deadrise distribution is the key to making a planing hull perform well.

What’s Deadrise?

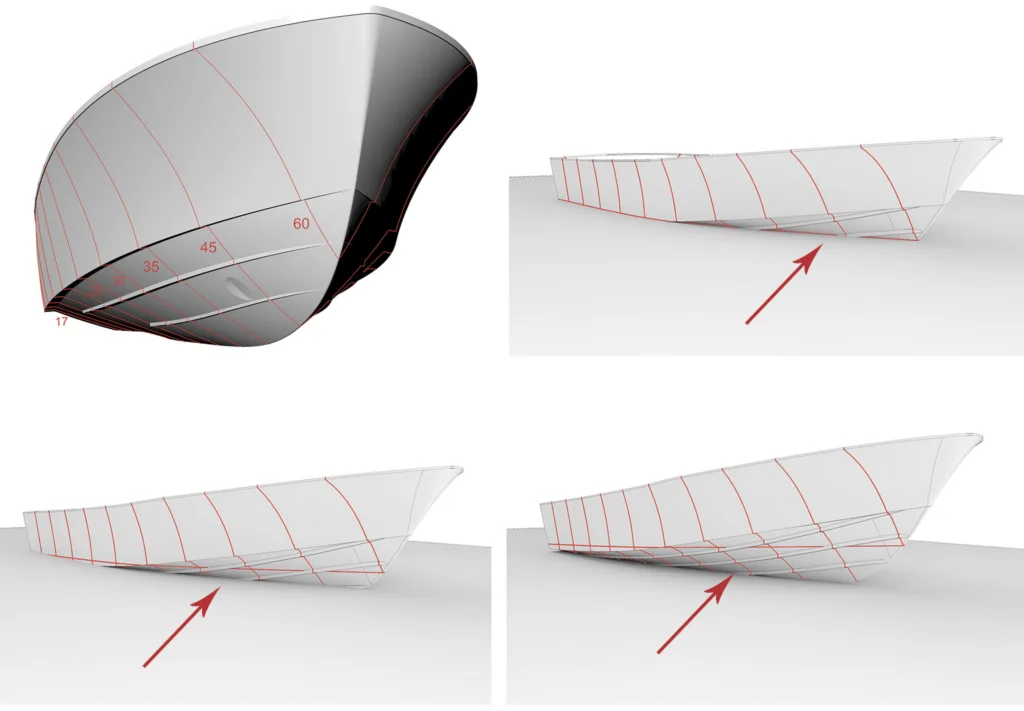

Deadrise is the angle between the bottom of the hull in relation to a horizontal plane as you go from the keel towards the chines. Unless it’s a flat-bottomed barge, if you imagine the boat sliced like a loaf of bread from bow to stern, the deadrise should vary.

In most boats, the deadrise in the bow of the boat is greater than at the stern. That’s because the bow is the first part of the hull to impact waves as the boat moves through the water. When a boat moves through the water at low speed, say up to 8 knots, the hull is displacing water rather than climbing up and planing on top of it. At low speed, the hull is at the same level as when it’s stopped, so the waves meet the bow all the way forward.

The boat is supported by buoyancy, which is a function of the weight of the water displaced by the hull in the water. The displaced water exactly equals the weight of the boat and all its contents. As power is applied and the boat starts to speed up, the boat starts to rise up on the surface of the water, increasingly supported by the dynamic pressure of water moving rapidly below the boat.

Now, the boat’s hull has to be shaped to create lift as its speed picks up. The after half of the hull should be nearly level with the surface of the water when at rest, so the stern doesn’t sink as power is applied.

This, in turn, means the transom must be immersed underwater when the boat is at rest, rather than swooping up like a ship or sailboat’s stern. It also helps that the hull has a sharp corner, or edge, at the chines, where the bottom meets the hull sides, and at the transom. The hard corners allow the water to break free of the hull when running at speed, creating flow separation and reducing resistance.

Variable Deadrise

The amount of deadrise at any given point in the hull changes as we move from the bow to the stern. More deadrise forward allows the hull to slice through waves with little or no pounding. Less deadrise aft allows the boat to climb up on plane with less energy and at lower speeds as power is applied.

Let’s say the deadrise is 45 degrees at the bow. If that deadrise continued all the way to the transom, the boat would not be able to get on plane because there wouldn’t be enough dynamic lift generated by water flow. The boat would also roll easily and deeply in even a light chop, and it would list to one side excessively when a person or heavy object moves from one side of the boat to the other.

On the other hand, if the hull is too flat in the bow, it will pound hard and incessantly, making the boat uncomfortable and even unusable unless it’s in flat water. If it’s too flat in the stern, the stern will just as readily move sideways as ahead, and it will be difficult to keep on course, especially when running downsea. Moderate deadrise aft helps keep the boat going straight, like a keel does on a lobster boat.

Deadrise distribution has to be sharp enough forward in a planing hull to create a smooth entry and part the waves to the side gently upon impact. The faster a boat can go, the more deadrise it needs farther aft in the hull, because higher speeds cause the hull to rise farther out of the water vertically. When this happens, wave impact shifts aft.

Faster hulls need more deadrise farther aft and in the middle of the hull. Go-fast boats can reach speeds of 100 mph or more. They jump from wave to wave, landing on the last few feet of the hull, so they need 24 or even 25 degrees of deadrise at the transom to absorb the shock of wave impact at those speeds. The center of gravity is also well aft in these boats, so the stern lands before the bow.

A slower boat cruising at 20 to 30 knots doesn’t need as much deadrise aft, since waves impact mostly at the middle of the hull, not the stern. Too much deadrise aft makes the boat slower and causes it to roll excessively. But even a slower planing hull needs some deadrise at the stern to give it directional stability. For boats that cruise at 25 to 35 knots, 20 degrees of deadrise at the transom creates plenty of lift, and it resists sideways movement aft when the boat is on plane. This helps keep the boat on course without excessive helm input.

If a bottom aft is flat like a shoebox, it will easily veer off course. Deadrise forward creates a smooth ride, and deadrise aft keeps the boat on course with less attention and effort at the wheel. This course-keeping attribute is especially important when running downsea, with the seas on the stern or on the quarter throwing the stern around.

A bad combination is a hull with a very sharp bow that turns into a rudder when running downsea, and a flat stern that has no resistance to sideways movement. This can make a boat uncontrollable when running downsea and can create a course-keeping circus. This can be dangerous when taken to extremes, since a yaw downsea can be followed by a roll and subsequently lead to a broach.

Deadrise Effect on Trim

Boats with monohedron hulls have the same deadrise from the middle of the hull back to the transom. These hulls can tend to run bow high and need oversize trim tabs to bring the bow down. If the chine is at the same depth from the middle of the hull to the stern sitting at the dock, it’s a monohedron.

A boat with chines that are deeper—that run downhill—as you move aft are said to have warp, or twist back aft. This shape shifts the center of dynamic lift aft as the boat gets on plane, so the boat will tend to run at the optimal trim without resorting to drag- inducing trim tabs or interceptors to get the bow down.

With the hull running naturally at a 3- to 4-degree trim angle, the engines on an outboard-powered boat can be trimmed up to the get the bow out of the water to reduce drag. A well-designedhull rarely needs trim tabs to correct running trim, only to correct for side-to-side imbalance caused by wind or offset weight.

Keeping the Bow Where it Belongs

A boat that runs bow high creates more drag, with a more deeply immersed transom displacing more water than it should. This adds resistance and increases fuel burn. It also produces a bigger wake, Bow-high trim also obscures the view forward from the helm, creating a dangerous operating condition. There is also a near-linear relationship between trim and slamming, so the more the bow goes up, the more it will pound.

Deadrise distribution from bow to stern is essential to a good-running boat. All planing hulls need 18 to 20 degrees of deadrise at the transom to keep the hull going straight, especially when running downsea.

Deadrise vs. Keels

With deadrise aft resisting sideways movement, the hull shape itself acts as a keel, but unlike a boat with a keel, a planing hull without a keel will heel, or lean, into a turn when running at speed. On the other hand, a boat with a keel will heel away from a turn, which has several negative effects.

A passenger on a planing boat in a turn that heels just the right amount will not know the boat is in a turn, at least in calm water. The boat will heel like an airplane or bicycle in a turn, cancelling out centrifugal force. This is very important for passenger safety reasons,. A boat that turns flat can throw people outboard, possibly causing injury or even ejecting them overboard. A boat with 20 degrees transom deadrise will lean into a turn and send centrifugal force down through your feet, keeping you stable. A boat with a full keel heels outboard in a turn, reducing stability for its passengers. Performance wise, keels are not appropriate for planing hulls that cruise much above 18 to 20 knots because they also add a lot of frictional resistance, absorbing propulsion energy. Although a keel is there to add stability, deadrise allows a boat to heel into a turn, thus making a boat safer for its passengers under this circumstance.

What It Means

A good-running boat is much more enjoyable, kinder to your body and helps prevent injuries. Your family and friends will want to go out on the boat. You will be able to go faster and farther in a given sea state. And you’ll be able to go out more often, when lesser boats stay tied to the dock.

Eric Sorensen is a consultant to boatbuilders and boat buyers. He is the author of Sorensen’s Guide to Powerboats: How to Evaluate Design, Construction and Performance.

April 2025

Little Harbor 60

Little Harbor Yachts is a renowned brand known for producing high-quality sailing yachts. Founded by Ted Hood in the 1950s, Little Harbor Yachts gained a reputation for building custom and semi-custom sailing yachts that were both luxurious and seaworthy. The company was based in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and produced a range of yachts, including the Little Harbor 38, 42, 44, 46, 53, and 58 models, among others. These yachts were highly regarded for their craftsmanship, performance, and elegant design, making them popular among sailing enthusiasts and cruising aficionados.

The Little Harbor 60 is a classic sailing yacht known for its luxurious accommodations and excellent sailing performance. These yachts are highly regarded for their craftsmanship and seaworthiness. The 60-foot model offers spacious living areas, typically featuring a master stateroom, guest cabins, a salon, and a well-equipped galley. The yacht’s design allows for comfortable cruising and often includes amenities such as a cockpit for outdoor dining and relaxation.

REDSTART, a central listing with Wellington Yacht Partners, is a pristine Little Harbor 44 Yacht with exceptional performance and shoal draft. This Hood-designed sailing yacht offers a shallow 5’ draft (centerboard up), built to high standards with electric winches and furling mainsail for easy short-handed sailing. Featuring a sought-after two-stateroom/two-head layout, REDSTART provides both privacy and versatility. With only two owners and limited summertime use, she’s been meticulously maintained, including inside winter storage and recent upgrades—new hull and mast paint, sails, electronics, and more. Perfect for those seeking a high-quality, pedigree sailing yacht at a competitive price!”

LAMLASH ~ SOLD in 2023 is a highly customized Little Harbor 58/60 model with one foot added to the standard 58 hull for a longer aft deck, draft reduced by 8” to only 4’ – 6” with centerboard up, and mast height slightly lower (20”) to provide 75’ bridge clearance. She is also one of only two in the series that features a centerline queen berth aft. Like her sisterships, LAMLASH can be easily sailed by one thanks to a cockpit design that is second to none – all sail controls and winches are at the helm, and easy side exits to main deck. She also boasts finely crafted joinerwork above and below decks that is seldom if ever seen in newer yachts today. VIDEO ~ Little Harbor 59 ~ LAMLASH

By Ted Hood

Managing Partner, Wellington Yacht Partners

[ped – i – gree] “distinguished, excellent…a continuous history or series or precedents, especially considered as evidence of respectability or legitimacy”

That old adage “They don’t build them like they used to,” is familiar to most and certainly applies to the current sailboat market. Anyone looking to buy a new boat today is limited to mostly mass-produced, modern-styled lookalike designs that often incorporate some innovative ideas and equipment, but are ultimately built with one goal: keeping costs down. That’s a great thing to attract new sailors to the market. But it also means high volume with limited options and low man hours, utilizing modern materials like man-made wood veneers and even faux wood trim.

For those looking for a higher level of detail and finish, where to go? There remain a very few good custom builders – such as Brooklin Boat Yard and Lyman Morse in Maine – where one can build a true “one-off” design to exacting standards after waiting 12-24 months for delivery.

Fortunately, there is another option that many of our clients have enjoyed with great satisfaction — the many fine semi-custom sailboats crafted during the peak building activity of the 80’s and 90’s. The four most iconic brands that stand out are Hinckley, Little Harbor, Alden and Bristol. Each design features a handsome shear line with relatively more overhang and a more traditional transom, typically with a keel/centerboard configuration that provides access to shallow waters while also preserving upwind performance. One will find a variety of layouts, equipment and interior woods, along with a mix of aft- and mid-cockpit versions available, depending on what one is looking for. Desirable features include custom stainless deck hardware, intricate exterior trim and exquisitely finished interior joiner work, often with raised-panel cabinetry and solid teak and holly floorboards.

Today, one would be hard pressed to find these qualities in most new boats, as the man hours required to build them would make any new boat cost-prohibitive. For example, a Little Harbor 54 typically required on average 18,000 man hours to complete in 1990, while a mass-produced Beneteau 55 requires less than 4,000 hours. The good news is, you can find a used Hinckley, Little Harbor, Alden or Bristol sailboat at a price that is just a fraction of its replacement cost.

We call them “pedigree sailboats” simply because they carry a solid reputation of quality, attention to detail and traditional design that cannot be duplicated today. There is a consistent following of sailors who appreciate and seek that pedigree and enjoy the pride of ownership that comes with it.

With our intimate knowledge of the design, construction and sailing characteristics of these fine yachts, our diverse team of brokers at Wellington is ready to assist you in your search.

By Bob Marston

Partner, Wellington Yacht Partners

Let’s face it, for a boater there are few things better than spending time on the water with friends and family. If you’re looking for space, liveability and a fun sailing platform, a catamaran may be the right choice for you.

There are essentially two types of sailing catamarans in the cruising market — those with dagger-boards and those with keels. Catamarans with dagger-boards tend to be designed for high-performance (i.e. fast) sailing, whereas those with fixed keels tend to have traditional sailing speeds.

Some of the production high-performance builders to consider are GUNBOAT, CATANA, OUTREMER and H&H. Common fixed-keel catamaran builders include SUN REEF, LAGOON, FOUNTAINE PAJOT, LEOPARD, and PRIVILEGE.

High-performance catamarans get their speed by limiting weight in construction, oftentimes by using high-tech materials like carbon fiber and including high-profile dagger-boards and rudders to assist with lift. They have large sail plans and can attain speeds in the teens, with some of the fastest options – like GUNBOATs – reaching 20-plus knots when pushed. Another advantage of dagger-boards is shallow-water access, as boards can be raised to access anchorages not accessible to keeled hulls. Offshore, this design can have less of a chance of “tripping” in heavy weather by raising the leeward dagger-board. Many owners of high-performance catamarans are good experienced sailors or hire professional crew to help eliminate the learning curve of a high-performance boat.

While fixed-keel cruising catamarans do not have the speed of high-performance catamarans, they do provide a very forgiving and comfortable cruising platform. These models have huge amounts of space for storage and living. Larger models have fly-bridge areas that offer great views while sailing and are an excellent place to relax and look around the anchorage when at rest. The sail plan of a fixed-keel catamaran tends to be a little more conservative, but still pushes the boat at normal sailing yacht speeds – in the range of 7 to 9 knots. While weight is always considered in the design of a catamaran, fixed-keel cats do not tend to have exotic materials such as carbon fiber, so they are less expensive to build and purchase. Other advantages of fixed-keel catamarans are protection of the hull underbody in the case of accidental grounding and more interior space, since dagger-board trunks do not have to be incorporated. It’s also nice to have the ability to block the boat when hauled out of the water on its own keels, whereas some of the performance-style catamarans, with their composite hull structures, require cradles or large blocks of foam for hull support when hauled out.

Throughout the spectrum of cruising catamarans available, there is something for every type of user. We are happy to share our knowledge and talk you through what might be best for your personal needs.

By Bob Marston

Partner, Wellington Yacht Partners

From 1999 to 2010 I had the pleasure of working as a salesman for Oyster Yachts in the Newport, RI, U.S. office. Under the vision and direction of founder Richard Matthews, the company grew and evolved to the successful brand it is today, recognized around the world as one of the best blue water cruising yachts available.

Oyster has earned its reputation through a continuous evolution of design, build integrity and responsiveness to feedback from its owners, who take their yachts to distant horizons.

In 1973 Oyster began with the constructions of a 32 foot cruiser/racer named the UFO. A successful design, UFO won most of the regattas it entered in 1974. Winning results soon brought more orders, and a boat-building company was formed. In the 1980s Oyster started to introduce cruising models like the 406, 46 and 49PH.

The success of these designs brought Oyster into the offshore cruising yacht scene. Their designer at the time was the firm of Holman and Pye, and many credit them for bringing the deck saloon concept to market. The model that put Oyster on the world cruising map was the Oyster 55 in 1989. Soon after its launch there were a number of Oyster 55s in the Blue Water Rally; it was here that the Oyster 55 gained notice and the deck saloon concept became a household name in cruising circles.

In the late 90s Don Pye was wishing to retire, so Oyster started the search for a new designer. They settled on Rob Humphreys, and in 1998 Rob designed the Oyster 56. The Oyster 56 Series was extremely successful, with 76 hulls built. Its characteristics were soon passed along to other new models in the line during the early 2000s: the Oyster 49, 53, 62, 66 and 82. These models were referred to as “G4” or Generation 4 designs. The construction of the yachts remained the same as they had been, with hand-laid solid glass layup, skeg-hung rudders and fin keels.

Around 2006 Oyster’s in-house design team along with Rob Humphreys was coming out with a new “G5” Generation 5 Design. These models were the Oyster 46, 54, 575, 655 and 72.

In the late 2000s, Oyster along with the Ed Dubois Design Team created the Oyster 100 and 125 Models, which remain the largest yachts Oyster has built to date.

Around this same time Oyster introduced the 625 and 885 with its “sea scape” hull windows. Taking the idea from their Super Yachts, they also included other features like flush-deck hatches and a single-point mainsheet to offer a cleaner deck layout.

The current generation of Oysters are the 565, 595, 675, 745 and 885. Refined features on these models are the integrated bowsprits for off-wind sails, European-style interior layout options with master cabin forward, tidy deck layouts and more modern interior design. While the 745 and 885 are crew-oriented yachts, the 565 and 595 are still intended as owner-operator models.

Oyster Yachts has never been a builder to sit on its laurels. Their success is derived from a creative in-house design team as well as from feedback from many happy owners all over the world sharing their experiences, both positive and negative. This feedback is then considered in the newer models, making Oyster yachts a constant evolution in progress.

Oysters are a brand we love to sell and have tremendous personal knowledge of. Please feel free to contact us to discuss all things Oyster.

By Bob Marston

Partner, Wellington Yacht Partners

In 1972 Tom Morris left his previous life in Philadelphia to pursue his passion of boat building. At that time I’m sure he wouldn’t have imagined his vision would someday result in the establishment of Morris Yachts, one of America’s finest yacht brands.

Tom Morris embarked on his craft building Friendship sloops in Southwest Harbor, Maine. He purchased the fiberglass hulls and decks from Jarvis Newman and fit out the boats under the Morris name. I remember his son Cuyler telling me how he and Tom would literally go into the woods and hand select the spruce trees to be used for the spars.

In 1974 Tom connected with designer Chuck Paine, who was promoting a new design. It was the Francis 26, a robust double ender with excellent sea handling characteristics, capable of sailing anywhere. As the relationship between Tom and Chuck grew, so did the model offerings with the Linda 28, Annie 29, Leigh 30 and the Justine 36 Series soon after.

In the late 1980s the company started to focus more on its cruising yachts. These were the Morris Ocean Series 38, 42, 44 and 46 Models. The Morris Ocean Series were great-performing, aft cockpit, trunk cabin style sailing yachts with pretty lines and exquisite craftsmanship. The success and quality of these designs soon gained recognition in the yachting community, and Morris Yachts found itself with owners throughout the world.

In 1999 Morris Yachts expanded their production capacity by purchasing the Able boatyard in Trenton, Maine. At the same time they added a series of Offshore Cruiser Racer models with the Morris Ocean 45, 48 and 52RS. One of the most notable boats was FIREFLY, a Morris Ocean Series 45, which did extremely well in distance races.

In 2004 Morris Yachts announced its Sparkman and Stephens designed Morris M36 that set the bar for the luxury day sailor market. The Morris M36’s beautiful over-hangs and low profile cabin top were an instant classic. A performance keel, spade rudder and fractional carbon rig made the M36 a pleasure to sail, and the huge cockpit was enough to take three couples for an afternoon sail easily.

The success of the Morris M36 soon spun off into other models… the Morris M29, Morris M42 and Morris M52. A standard feature of all the M Series was the ability for the helmsman to handle all control lines from the wheel, making the yachts truly able to be singlehanded, while keeping guests in the cockpit free from entanglement.

After some 45 years of boat building, one thing is for certain: The Morris Family is passionate about sailing, and anyone who has had the chance to get aboard a Morris Yacht will agree.

At Wellington Yacht Partners we know Morris Yachts and their clientele well. We are happy to discuss the differences between models and share our own experiences with these fine yachts.